Welcome to the latest installment in our series of interviews with women who are transforming the world of design and development and inspiring us every day.

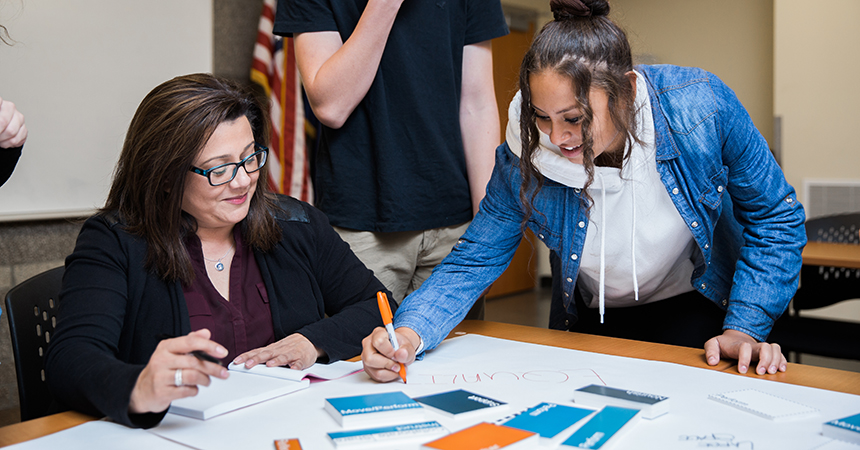

As one of the founding principals at BRIC Architecture in Portland, Karina Ruiz approaches her work with empathy and understanding for the students and families with whom she co-creates learning environments. Rooted in social equity and environmental sustainability, Ruiz’s projects empower communities to create spaces where people can not only learn—but thrive. Beyond her work with BRIC, Ruiz is a founding member of the National Organization of Minority Architects Portland Chapter where she supports local creatives and works to amplify underrepresented experiences in the design community.

Q: Can you describe your work?

I am one of three founding principals at BRIC Architecture in Portland. BRIC stands for “Building Relationships and Inspiring Communities.” We chose this name rather than one of our founders’ names because it represents the importance of relationships in our work. As one of Oregon’s largest woman majority-owned architecture firms, we practice architecture differently. At BRIC, I work alongside communities to reimagine learning environments so that they can help make the world a more equitable, just and humane place.

We’ve designed our way to where we find ourselves now—and it’s no accident we are seeing so many societal and environmental inequities. I believe schools have the power to change societies and lives, one generation at a time. With empathic design, we can design our way to a better world. And through intentional design, we can lend a voice and empower marginalized communities to co-create schools that will have a deep impact on future generations.

Q: Why is sustainability central to your career?

I’ve focused my career on creating sustainable learning environments because I believe we have a moral imperative to foster the next generation of environmental stewards. It’s important to recognize that we can’t talk about environmental sustainability without talking about social equity. Often, the people who are most impacted by pollution are the people with the least resources. When we design schools, it’s our mission to ensure that we aren’t just going down a LEED checklist, but that we’re looking holistically at how this work can support families and students economically, socially and environmentally.

When I was touring students and their families through the newly-opened Trillium Creek Primary School, I remember students pointing out sustainable features to their parents—such as the natural resource meters and the natural ventilation indicators—and how they could implement similar, simple changes at home to be more sustainable.

To me, sustainability is such a beautiful word. When I think about sustainability, I think about how we treat each other. I think about how we work together to make our profession and our firm sustainable. And I think about how we help each other thrive. If you want to stay relevant and continue to have an impact, then you need to care about sustainability.

Q: What are the biggest challenges you’ve faced in advancing sustainability efforts in your field?

The biggest challenge we face is the inequitable distribution of resources. For example, in Oregon, property taxes are the way communities build themselves up. In communities with lower socioeconomic levels, it can be harder to pass bonds to improve schools. Sustainable school design can have major cost savings for schools—but the ability to fund those improvements in the first place can be challenging for many communities. Energy Trust of Oregon can be a lever to help districts that don’t have access to major capital improvement bonds make sustainability improvements.

Q: What changes have you seen, or do you expect to see, in your industry as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic?

I have been appreciative and in awe of the way schools have had to adapt. The pandemic has been a huge disrupter in making things happen that we didn’t think were possible before the lockdown.

In terms of educational architecture, we are seeing an increased focus on air filtration and ventilation. I also see more design professionals deepening their understanding of the roles that schools play in our communities. During the pandemic, we saw schools emerge as critical hubs for food distribution and mental health resources. From a design perspective, we need to focus on continuing to leverage the schoolhouse as a social connector and a safety net for families.

While this was prior to the pandemic, I still remember when I visited Rosa Parks Elementary School after it had opened and heard parents in the Family Resource Center we had designed for them sharing how important it was to learn alongside their children. The pandemic has only renewed my realization of the power our work has in impacting the whole child, the whole family and the whole community.

Q: What excites you most about the future of your work?

More so than at any other time in my career, we’re at an inflection point. We can go back to how things were or choose to take the lessons we’ve learned in the last year (and years before that) to co-create a better world.

I am excited to see architects thinking differently about the processes we use, the people we advocate for, and the resources we leverage to pull the “arc of the moral universe” more acutely towards justice. We need to rethink everything we know about design to make our vision of the world a reality.

Q: What is your advice to women entering your field?

Find something that fuels your passion and do it. There is demand on all of us, but especially on women to balance your family and career. Finding something you love can help bring forth that balance. If what you love doesn’t exist, create it—that’s what we did at BRIC. I also think it’s important to find your voice and find mentors. And remember: Pull up your sister next to you so we, as a society, can advance better together.