This is part of a series of blog posts amplifying community voices.

Growing up in Portland, OR Chandra Robinson’s love for the outdoors started early, leading to years as a sea kayaking guide and the study of geology and physics. Always drawn to architecture, she developed a deep appreciation for spaces that felt welcoming and comfortable. Today she’s a Principal at LEVER Architecture, based in Portland and Los Angeles, where she is proud to create impactful spaces that are accessible for all.

As a Founding Board Member and Treasurer of Noma PDX, Chandra works to bring together people of color in architecture, design and construction, and addresses social equity and inclusion in sustainable design.

Q: What drew you to architecture?

I knew I wanted to be an architect since I was about six years old. I was always thinking about houses and imagining ones I wanted to create. My family is full of artists—my brother is a musician and my sister is in theater production—so the urge to create was all around me.

Q: How has the profession continued to drive you?

When you go to architecture school you don’t necessarily feel you have the power to change things because you assume you’ll be catering to client wants and needs. But once I had my feet under me in the profession, it became a collaboration. I learned that I have a lot to contribute by deeply listening to the voices of people who will be using the spaces I design and coming up with creative solutions to meet their needs. Collaboration also removes some pressure—we’re all working together to make something great.

Today, what really drives me is asking: “What’s next?” I’m inspired by seeing the industry grow and challenge itself. A lot more firms are pushing technologies further with each project they complete, with greater efficiency and better materials—asking questions like: “Can we go up another floor?” or “Can we do it faster?”

Q: What role does the natural environment play in your work?

I value natural materials that are local, and that support rural economic development and enterprises that are minority- or women-owned. We have to take care of the communities in which we’re building, as well as those from which we’re sourcing materials. It’s not just about lower electric bills and cleaner indoor air for clients, but also intentional forest management rather than extractive and damaging methods.

In terms of bringing the natural environment into my designs, I love wood because it creates a warm atmosphere. It’s very tactile, room temperature, and has a bright quality that makes spaces more calming and soothing. Our firm also tries to make access to views and daylight equitable across the buildings we design, which can be a challenge in larger spaces with lots of desks.

Q: Do you face challenges in advancing sustainability efforts in your field?

I’m from Oregon and have always felt we’re ahead of the curve with sustainability, so it’s not a question of whether to do it within architecture, but how. How can we show a client that upfront costs for sustainable design will have payoffs? How do we do it at scale, especially with high-quality materials? Things like low-VOC paints and FSC-certified wood come with a small premium; they are more than worth prioritizing.

Q: What, and who, inspires you?

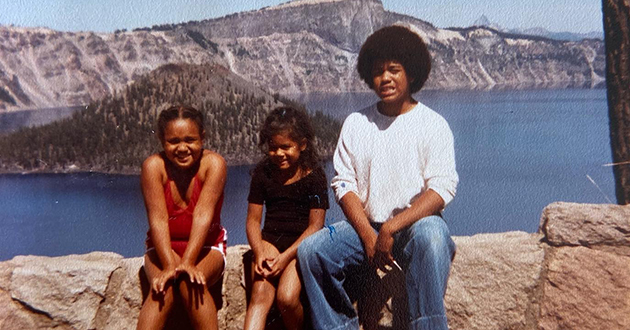

My mother always said, “You can do anything,” which gave me the freedom to study different things (including geology and physics before I went to architecture school) and switch paths. She was very supportive. She had stopped going to college when she became a mom but went back while I was at Portland State University for my undergrad, and we graduated at the same time.

Q: What, in your opinion, are the biggest challenges facing your firm, or the field of architecture as a whole?

Trying to include good design in affordable housing is a financial challenge, but I think of it more as a requirement. Everyone deserves interior spaces that are comfortable, well-ventilated and healthy.

Taking the time to engage communities in projects can also be seen as a challenge, but it’s crucial to include the people who will be using the schools, libraries and housing we build. We need to engage them in design conversations and ask them how they define improvement for their community, and who is represented or not represented, or burdened or not burdened by changes. That’s the most responsible, holistic way to make spaces that are of real, serviceable value.

Q: What advice do you have for women or people of color who are interested in architecture or related fields?

Sometimes you have to really search to find people who look like you in this field, but we’re here, and we want to help others come up and succeed, and to become part of this professional community. Noma PDX is one place to find mentors and a cohort; it’s an energetic organization that’s bringing together people of color in architecture, design and construction. I also do talks at architecture schools and try to be visible and accessible as a connection to the field for students, whether they need someone to look at their portfolio or point them towards an internship.

As for those already in the field, I don’t think you should stay somewhere too long if you’re not given opportunities to advance your skills. Advocate for yourself, and if you have to move on, that’s OK. Work for paths to leadership, promotion and experience. Mentors can talk you through these kinds of things—what skill level you should be at and what you should be paid.

We need diverse talent to stay in Portland and keep increasing representation. If these young people feel alone, like they don’t have cohorts, they’ll leave. We need them to stay and have careers that reward them and challenge them.