This is a part of a series of blog posts amplifying community voices. These views reflect the perspective of the Changemaker and do not necessarily represent those of Energy Trust.

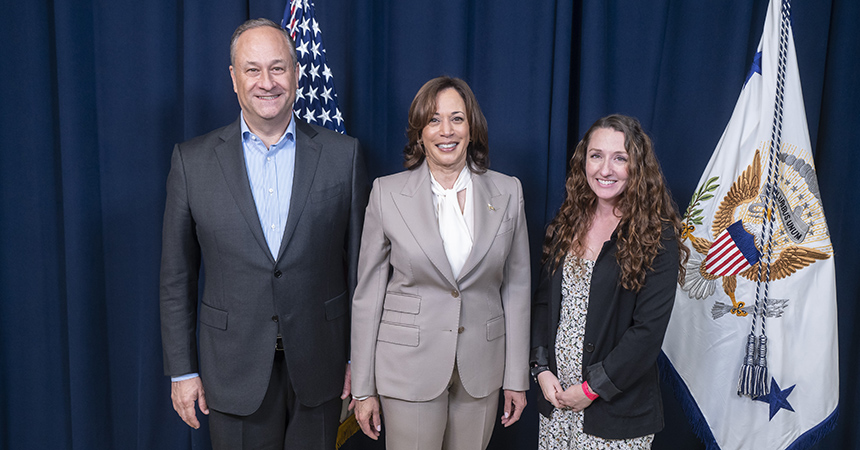

As Associate Director of Leadership and Market Development at the nonprofit New Buildings Institute, Reilly Loveland is a national leader in sustainable school infrastructure. She facilitates net-zero-energy school retrofits and K-12 sustainability initiatives. While growing up, she wanted to be a teacher – and now, her role puts her in conversation with architects, engineers, school facilities managers, teachers and even students – all to make sure schools are as comfortable and energy efficient as possible. She has served as co-chair of the U.S. Green Building of Council’s Green Schools program, and worked with Integrated Design Lab and EarthGen (formerly Washington Green Schools) on research and curriculum development.

What inspired you to focus on sustainability in your career, rather than other sectors?

I really like rocks, dirt, and the environment. My degree is in Geophysics and Environmental Science, and later I got certifications in Real Estate, ArcGIS, LEED, and Green Classroom Professional. After college I was originally headed straight to the oil companies for my first job. But I got hired at a firm that did some energy efficiency work, and I was tasked with gathering energy-use data for Washington state school districts. The connections with people in the schools are what drew me in and got me hooked on energy use and conservation – especially in schools.

I had wanted to be a teacher at one point; something always pulled me to work with K-12 students. So, both interacting with students and teachers and doing some in-depth data analysis really cemented my interest in this field.

When I worked for EarthGen (formerly Washington Green Schools), I participated in school assemblies and other events that got kids thinking about energy use and sustainability. Kids take home the lessons they learn in school, which can influence their families to think more about sustainability. Seeing students grow and become leaders of sustainability was really impactful.

How does your work managing school-stakeholder engagement coexist with the roles of engineers and architects on a given project?

I have a unique in-between role, facilitating sustainability initiatives. I translate learnings and the desired outcomes from the users and owners of a building to the architecture and engineering community. I listen, watch, and share my findings and the perspectives of the internal stakeholders so that everyone is on the same page and can move forward on a project.

What’s a valuable skill that you’ve developed working with multiple stakeholders on projects?

Change management is a big one. I’ve learned to try to understand what others are doing and thinking, and to help them see change as a positive thing that can get us to a mutually beneficial outcome. For instance, what does a return on investment look like? Does it always have to be looked at through a financial lens? Or is the financial commitment to healthier classrooms a return on investment in itself because healthier classrooms mean students are healthier and better able to learn, and can help avoid school closures from heat and cold?

What makes a classroom healthy?

Air quality and temperature control are big factors. There are studies that clearly show that our brains react slower and our lung function is impacted when there is too much CO2 or other pollutants in the air. If your school is near a freeway or in an area affected by wildfire smoke, having the right air filtration and ventilation is essential.

Access to natural light and outdoor views such as classrooms with views of green spaces has been shown to boost student focus, reduce stress and improve academic performance. And of course, there are the building materials like nontoxic paint, ceiling tiles and flooring. Even having enough space to walk around, or different learning areas within a classroom or school building is important. Being able to move easily around a space, or find a space that fits student needs in that moment is conducive to learning. We are all different people with different needs to help us move throughout the day.

How do schools’ energy needs differ from other building types, and how do you address them?

Schools usually have unique energy loads, some are quite significant like meal-preparation and facilities like a kiln or an auto shop. Schools often also have different community needs and may need to run extended hours such as voting sites, community safe sites or cooling centers. We can’t just do one net-zero school template because every community, its needs, and its climate are unique.

The movement I enjoy most in schools are schools that focus on resiliency and may have battery storage, microgrids and solar. When power outages occur in neighborhoods or towns, schools can become warming centers and places for food distribution, if they have solar power. My neighborhood experienced a devastating ice storm, and we were without power for a week. Community sites with access to charging and warm spaces were crucial. I hope more and more schools are designed to fill this need.

What role do you think schools play in modeling environmental responsibility for students and communities?

They can play a huge role. Schools are one of the main public fixtures that people interact with. Something like one in three people interact with schools daily, nationwide, as students, parents, employees or neighborhood residents. When schools prioritize health and air quality, people will pick up on it and want these features in their homes and workplaces. A school district with healthy buildings can inspire cities to upgrade other infrastructure.

Not everyone can afford the green energy transition, but schools have the opportunity to be leaders in this area, and places for underserved populations to experience healthy buildings. Students could be inspired to take relevant career paths, creating a ripple effect.

When you envision the future of educational facilities, what excites you most?

While school infrastructure is underfunded, there is still a lot of momentum for reducing energy bills with prioritizing efficiency upgrades, and putting solar and geothermal systems into place. Folks are also seeing that indoor air quality is hugely important — a strange silver lining of the pandemic — so there are more upgrades being made to air filtration and ventilation systems.

Obviously, we have a stronger interest in decarbonization in Portland, to make building retrofits, new construction and demolition more sustainable. But it’s happening in a lot of other places, as well. I work with a woman who runs a school sustainability program in Lincoln, NE, where they focus on energy efficiency, geothermal systems and construction waste management. They don’t call it decarbonization, which is understandable; it’s not an approachable word. But that’s exactly what they’re doing.

If you could go back and give your younger self advice about your career path, what would you say?

I wouldn’t change my trajectory. I really like how it’s turned out. I get to work at a nonprofit, be creative, and I get to help people. But I would tell my younger self not to fixate on small stuff — or to either let it go, or address it head on. Small human interactions that don’t go well can feel upsetting in the moment. But often, with a little time, you realize they didn’t matter as much as they seemed.